By the 1950s and 1960s long-term hospitalisation attracted increasing criticism for its repressiveness and detrimental effects on the patients (Goffman, 1968; Houston, 1955), stimulating a national move away from the large mental hospitals.

In his 1961 ‘Watertower speech’ Health Minister Enoch Powell laid out his plans for the reorganisation of mental health treatment in the UK. These included drastic cuts to the number of beds and the integration of mental health services into general hospitals. He based the 1962 National Hospital Plan for England and Wales that introduced the cuts solely on the results and statistical predictions of one study (Tooth & Brooke, 1961). According to this, the DCMH, then known as Exe Vale Hospital and combined with Digbys and Wonford House, was expected to almost halve the number of beds by 1975 and the hospital eventually fell victim to the closure plans in 1987.

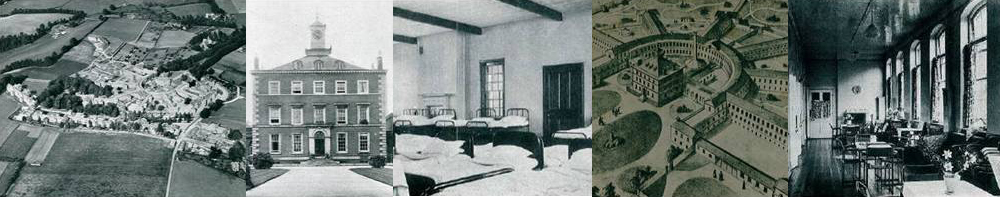

While the former buildings of the DCLA and Digby’s have been converted into apartments, Wonford House has since been acting as headquarter of the Devon NHS Trust, providing specialist services amongst others for people suffering from eating disorders.

Devon currently has beds available for the treatment of acutely disturbed patients, provisions for the chronically mentally ill are much bleaker with long waiting lists. A report commissioned by the Devon Primary Care Trust found that, although ‘internationally renowned for its deinstitutionalisation in the 1980s, efforts to continue the process seem to have stalled [in Devon]’ (o’Hagan, 2008). The report, which also takes into account service users’ views acknowledges that recovery has been put highly on Devon’s mental health strategy, but criticises that ‘home-based treatment […] sometimes amounted to just a daily phone call or a visit to give people their medication’, a fact the Trust envisages to remedy by 2015.